Following on from various other similar events we organised over the past few years, last week we hosted our largest ethical hacking competition yet, Cambridge2Cambridge 2017, with over 100 students from some of the best universities in the US and UK working together over three days. Cambridge2Cambridge was founded jointly by MIT CSAIL (in Cambridge Massachusetts) and the University of Cambridge Computer Laboratory (in the original Cambridge) and was first run at MIT in 2016 as a competition involving only students from these two universities. This year it was hosted in Cambridge UK and we broadened the participation to many more universities in the two countries. We hope in the future to broaden participation to more countries as well.

Cambridge 2 Cambridge 2017 from Frank Stajano Explains on Vimeo.

We assigned the competitors to teams that were mixed in terms of both provenance and experience. Each team had competitors from US and UK, and no two people from the same university; and each team also mixed experienced and less experienced players, based on the qualifier scores. We did so to ensure that even those who only started learning about ethical hacking when they heard about this competition would have an equal chance of being in the team that wins the gold. We then also mixed provenance to ensure that, during these three days, students collaborated with people they didn’t already know.

Despite their different backgrounds, what the attendees had in common was that they were all pretty smart and had an interest in cyber security. It’s a safe bet that, ten or twenty years from now, a number of them will probably be Security Specialists, Licensed Ethical Hackers, Chief Security Officers, National Security Advisors or other high calibre security professionals. When their institution or country is under attack, they will be able to get in touch with the other smart people they met here in Cambridge in 2017, and they’ll be in a position to help each other. That’s why the defining feature of the event was collaboration, making new friends and having fun together. Unlike your standard one-day hacking contest, the ambitious three-day programme of C2C 2017 allowed for social activities including punting on the river Cam, pub crawling and a Harry Potter style gala dinner in Trinity College.

In between competition sessions we had a lively and inspirational “women in cyber” panel, another panel on “securing the future digital society”, one on “real world pentesting” and a careers advice session. On the second day we hosted several groups of bright teenagers who had been finalists in the national CyberFirst Girls Competition. We hope to inspire many more women to take up a career path that has so far been very male-dominated. More broadly, we wish to inspire many young kids, girls or boys, to engage in the thrilling challenge of unravelling how computers work (and how they fail to work) in a high-stakes mental chess game of adversarial attack and defense.

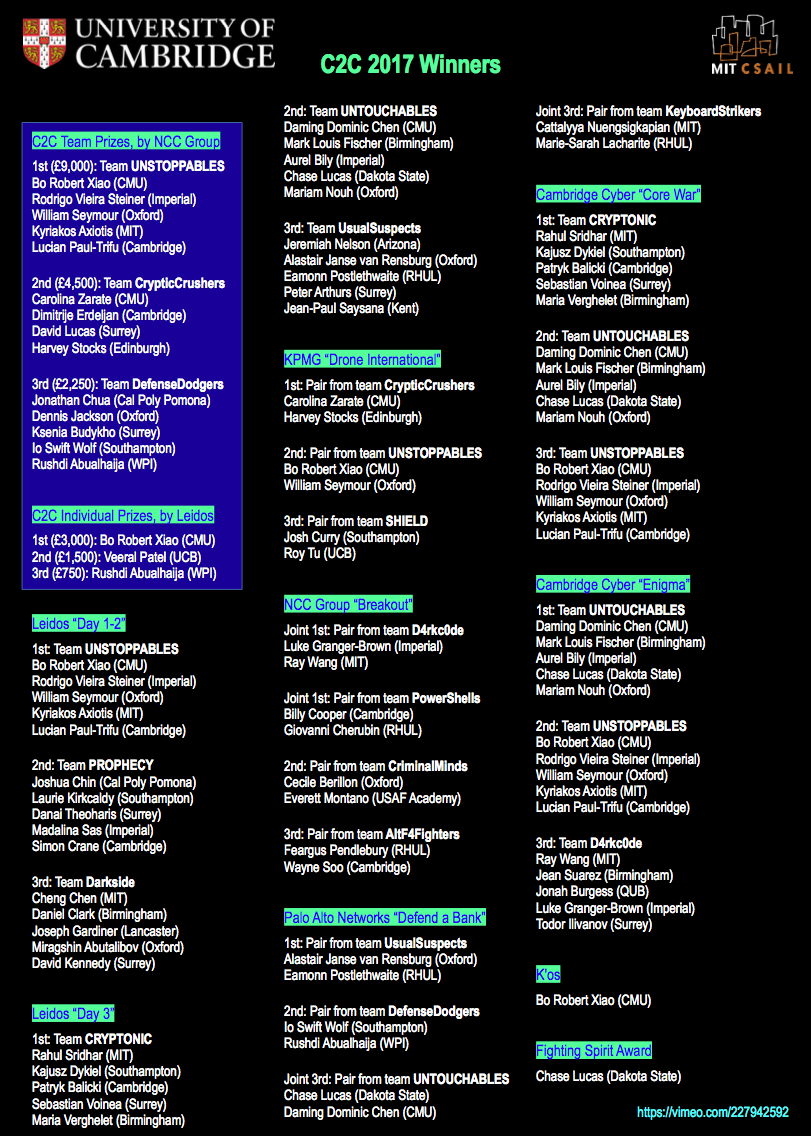

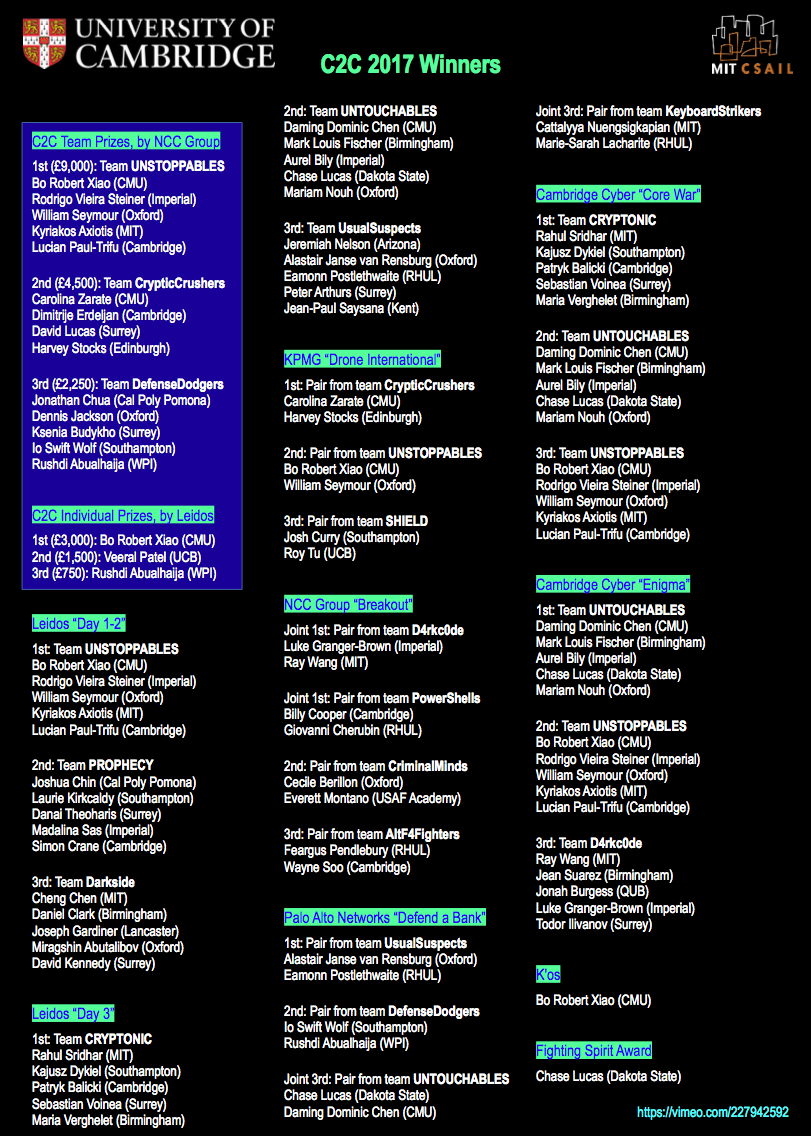

Our platinum sponsors Leidos and NCC Group endowed the competition with over £20,000 of cash prizes, awarded to the best 3 teams and the best 3 individuals. Besides the main attack-defense CTF, fought on the Leidos CyberNEXS cyber range, our other sponsors offered additional competitions, the results of which were combined to generate the overall teams and individual scores. Here is the leaderboard, showing how our contestants performed. Special congratulations to Bo Robert Xiao of Carnegie Mellon University who, besides winning first place in both team and individuals, also went on to win at DEF CON in team PPP a couple of days later.

We are grateful to our supporters, our sponsors, our panelists, our guests, our staff and, above all, our 110 competitors for making this event a success. It was particularly pleasing to see several students who had already taken part in some of our previous competitions (special mention for Luke Granger-Brown from Imperial who earned medals at every visit). Chase Lucas from Dakota State University, having passed the qualifier but not having picked in the initial random selection, was on the reserve list in case we got funding to fly additional students; he then promptly offered to pay for his own airfare in order to be able to attend! Inter-ACE 2017 winner Io Swift Wolf from Southampton deserted her own graduation ceremony in order to participate in C2C (!), and then donated precious time during the competition to the CyberFirst girls who listened to her rapturously. Accumulating all that good karma could not go unrewarded, and indeed you can once again find her name in the leaderboard above. And I’ve only singled out a few, out of many amazing, dynamic and enthusiastic young people. Watch out for them: they are the ones who will defend the future digital society, including you and your family, from the cyber attacks we keep reading about in the media. We need many more like them, and we need to put them in touch with each other. The bad guys are organised, so we have to be organised too.

The event was covered by Sky News, ITV, BBC World Service and a variety of other media, which the official website and twitter page will undoubtedly collect in due course.